Nigeria’s top 10 commercial banks spent a combined ₦377.85 billion on levies to the Asset Management Corporation of Nigeria (AMCON) and the Nigeria Deposit Insurance Corporation (NDIC) in the first quarter of 2025, representing a 34.6% increase from the ₦280.67 billion recorded during the same period in 2024.

This figure, drawn from unaudited financial statements for Q1 2025 filed with the Nigerian Exchange Limited (NGX), underscores the growing financial burden banks shoulder in meeting regulatory obligations meant to safeguard the stability of the financial system.

The banks surveyed include FBN Holdings Plc, Zenith Bank Plc, Guaranty Trust Holding Company Plc (GTCO), United Bank for Africa Plc (UBA), Access Holdings Plc, Fidelity Bank Plc, Wema Bank Plc, Stanbic IBTC Holdings Plc, Sterling Financial Holdings Company Plc, and FCMB Group Plc.

Breakdown of Regulatory Expenses

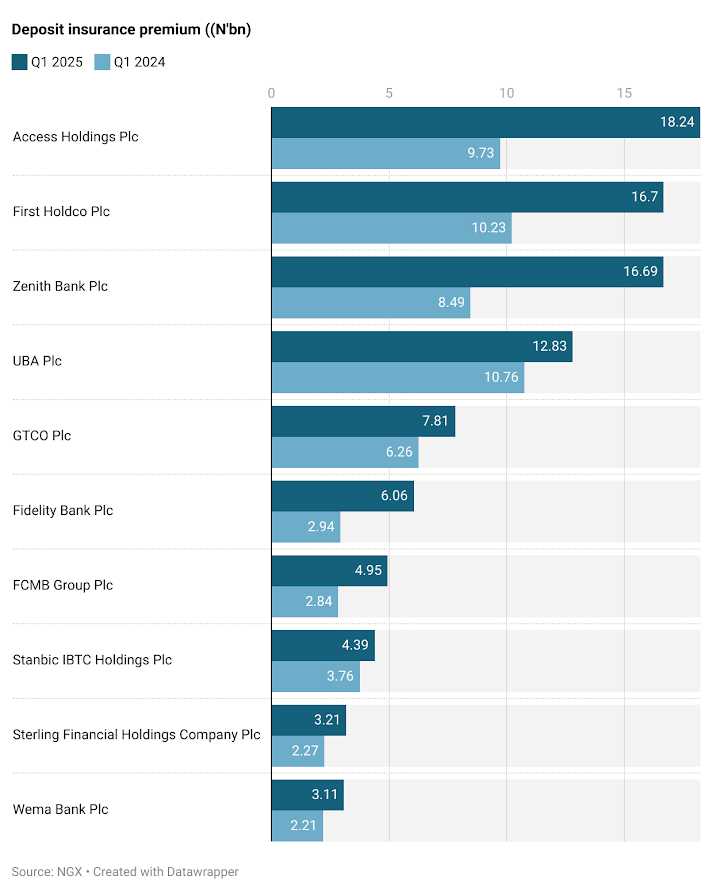

According to the results, the banks collectively paid ₦283.85 billion in AMCON levies during Q1 2025, a 28% increase compared to ₦221.2 billion in the same period of 2024. Additionally, the NDIC deposit insurance premium surged 58% from ₦59.5 billion to ₦93.99 billion year-on-year.

Despite these rising costs, the banks reported a combined profit before tax of ₦1.58 trillion, reflecting a modest 0.36% increase over ₦1.51 trillion in Q1 2024.

The AMCON levy, based on the 0.5% of total assets and 0.3% of contingent liabilities, is drawn from banks’ total balance sheet size in line with the AMCON Act of 2015. The NDIC premium, meanwhile, is a statutory insurance payment designed to guarantee depositor funds—now up to ₦5 million per depositor—in case of bank failure.

Zenith Bank, Access Holdings Top Contributors

Zenith Bank recorded the highest AMCON levy for Q1 2025, paying ₦71.92 billion, up 56% from ₦46.22 billion in Q1 2024. With total assets of ₦32.4 trillion as of March 2025, the bank also paid ₦16.68 billion in NDIC premiums—up 97% from ₦8.49 billion a year earlier.

Access Holdings paid the highest NDIC premium, remitting ₦18.24 billion, nearly doubling the ₦9.7 billion paid in Q1 2024. However, the group’s AMCON levy declined by 30.58% to ₦38.95 billion from ₦56.11 billion, following a 5.8% drop in total assets to ₦38.99 trillion in March 2025 from ₦41.4 trillion at the end of 2024.

The AMCON Controversy

Established in 2010 to stabilize Nigeria’s banking system during the financial crisis, AMCON was created to acquire and resolve non-performing loans (NPLs) from troubled banks. It is financed through loan recoveries, Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) contributions, and a sinking fund sustained by annual bank levies.

Initially, banks were required to contribute 0.3% of total assets, but this was increased to 0.5% in 2013, a move that has drawn growing criticism from industry stakeholders who argue that AMCON has outlived its usefulness.

Investment banker and stockbroker Mr. Tajudeen Olayinka criticized the agency’s continued existence, stating: “The endless yearly levies suggest AMCON is unable to meet its debt obligations. Its creation may have been a misplaced resolution strategy at the time.”

Mrs. Bisi Bakare, President of the Pragmatic Shareholders Association, echoed similar sentiments, questioning AMCON’s debt recovery performance and describing the agency as a drain on shareholders’ value.

However, Mr. Aruna Kebira, MD/CEO of Globalview Capital Limited, maintained that AMCON’s continued operation is a legal matter: “Its tenure and operations are defined by law. Whether it has overstayed its welcome is a matter for the federal government to decide.”

Mr. David Adonri, Vice President at Highcap Securities, offered a more contextual view: “AMCON was a necessary ‘bad bank’ solution to clean up the books of Nigerian banks post-crisis. Its levies are part of the agreed sinking fund established to redeem zero-coupon bonds issued for NPL clean-up.”

Conclusion

As regulatory levies continue to climb, stakeholders remain divided on the long-term viability and impact of AMCON’s role in Nigeria’s financial system. While its mandates were originally time-bound, its enduring presence—and cost to the banking sector—raises critical questions about reform, efficiency, and the future of financial system stability mechanisms in Nigeria.